- Log in to:

- Community

- DigitalOcean

- Sign up for:

- Community

- DigitalOcean

Introduction

OAuth 2 is an authorization framework that enables applications — such as Facebook, GitHub, and DigitalOcean — to obtain limited access to user accounts on an HTTP service. It works by delegating user authentication to the service that hosts a user account and authorizing third-party applications to access that user account. OAuth 2 provides authorization flows for web and desktop applications, as well as mobile devices.

This informational guide is geared towards application developers, and provides an overview of OAuth 2 roles, authorization grant types, use cases, and flows.

Deploy your frontend applications from GitHub using DigitalOcean App Platform. Let DigitalOcean focus on scaling your app.

OAuth Roles

OAuth defines four roles:

- Resource Owner: The resource owner is the user who authorizes an application to access their account. The application’s access to the user’s account is limited to the scope of the authorization granted (e.g. read or write access)

- Client: The client is the application that wants to access the user’s account. Before it may do so, it must be authorized by the user, and the authorization must be validated by the API.

- Resource Server: The resource server hosts the protected user accounts.

- Authorization Server: The authorization server verifies the identity of the user then issues access tokens to the application.

From an application developer’s point of view, a service’s API fulfills both the resource and authorization server roles. We will refer to both of these roles combined, as the Service or API role.

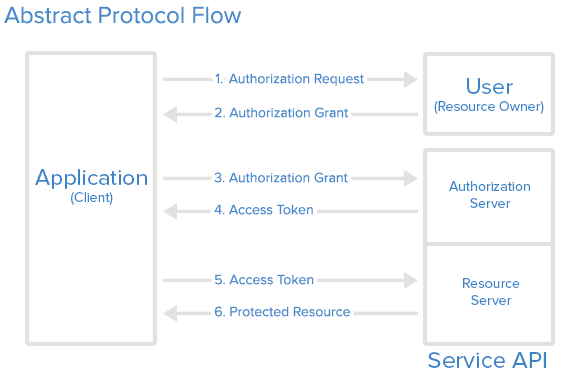

Abstract Protocol Flow

Now that you have an idea of what the OAuth roles are, let’s look at a diagram of how they generally interact with each other:

Here is a more detailed explanation of the steps in the diagram:

- The application requests authorization to access service resources from the user

- If the user authorized the request, the application receives an authorization grant

- The application requests an access token from the authorization server (API) by presenting authentication of its own identity, and the authorization grant

- If the application identity is authenticated and the authorization grant is valid, the authorization server (API) issues an access token to the application. Authorization is complete.

- The application requests the resource from the resource server (API) and presents the access token for authentication

- If the access token is valid, the resource server (API) serves the resource to the application

The actual flow of this process will differ depending on the authorization grant type in use, but this is the general idea. We will explore different grant types in a later section.

Application Registration

Before using OAuth with your application, you must register your application with the service. This is done through a registration form in the developer or API portion of the service’s website, where you will provide the following information (and probably details about your application):

- Application Name

- Application Website

- Redirect URI or Callback URL

The redirect URI is where the service will redirect the user after they authorize (or deny) your application, and therefore the part of your application that will handle authorization codes or access tokens.

Client ID and Client Secret

Once your application is registered, the service will issue client credentials in the form of a client identifier and a client secret. The Client ID is a publicly exposed string that is used by the service API to identify the application, and is also used to build authorization URLs that are presented to users. The Client Secret is used to authenticate the identity of the application to the service API when the application requests to access a user’s account, and must be kept private between the application and the API.

Authorization Grant

In the Abstract Protocol Flow outlined previously, the first four steps cover obtaining an authorization grant and access token. The authorization grant type depends on the method used by the application to request authorization, and the grant types supported by the API. OAuth 2 defines three primary grant types, each of which is useful in different cases:

- Authorization Code: used with server-side Applications

- Client Credentials: used with Applications that have API access

- Device Code: used for devices that lack browsers or have input limitations

Warning: The OAuth framework specifies two additional grant types: the Implicit Flow type and the Password Grant type. However, these grant types are both considered insecure, and are no longer recommended for use.

Now we will describe grant types in more detail, their use cases and flows, in the following sections.

Grant Type: Authorization Code

The authorization code grant type is the most commonly used because it is optimized for server-side applications, where source code is not publicly exposed, and Client Secret confidentiality can be maintained. This is a redirection-based flow, which means that the application must be capable of interacting with the user-agent (i.e. the user’s web browser) and receiving API authorization codes that are routed through the user-agent.

Now we will describe the authorization code flow:

Step 1 — Authorization Code Link

First, the user is given an authorization code link that looks like the following:

https://cloud.digitalocean.com/v1/oauth/authorize?response_type=code&client_id=CLIENT_ID&redirect_uri=CALLBACK_URL&scope=read

Here is an explanation of this example link’s components:

- **https://cloud.digitalocean.com/v1/oauth/authorize**: the API authorization endpoint

- client_id=client_id: the application’s client ID (how the API identifies the application)

- redirect_uri=CALLBACK_URL: where the service redirects the user-agent after an authorization code is granted

- response_type=code: specifies that your application is requesting an authorization code grant

- scope=read: specifies the level of access that the application is requesting

Step 2 — User Authorizes Application

When the user clicks the link, they must first log in to the service to authenticate their identity (unless they are already logged in). Then they will be prompted by the service to authorize or deny the application access to their account. Here is an example authorize application prompt:

This particular screenshot is of DigitalOcean’s authorization screen, and it indicates that Thedropletbook App is requesting authorization for read access to the account of manicas@digitalocean.com.

Step 3 — Application Receives Authorization Code

If the user clicks Authorize Application the service redirects the user-agent to the application redirect URI, which was specified during the client registration, along with an authorization code. The redirect would look something like this (assuming the application is dropletbook.com):

https://dropletbook.com/callback?code=AUTHORIZATION_CODE

Step 4 — Application Requests Access Token

The application requests an access token from the API by passing the authorization code along with authentication details, including the client secret, to the API token endpoint. Here is an example POST request to DigitalOcean’s token endpoint:

https://cloud.digitalocean.com/v1/oauth/token?client_id=CLIENT_ID&client_secret=CLIENT_SECRET&grant_type=authorization_code&code=AUTHORIZATION_CODE&redirect_uri=CALLBACK_URL

Step 5 — Application Receives Access Token

If the authorization is valid, the API will send a response containing the access token (and optionally, a refresh token) to the application. The entire response will look something like this:

{"access_token":"ACCESS_TOKEN","token_type":"bearer","expires_in":2592000,"refresh_token":"REFRESH_TOKEN","scope":"read","uid":100101,"info":{"name":"Mark E. Mark","email":"mark@thefunkybunch.com"}}

Now the application is authorized. It may use the token to access the user’s account via the service API, limited to the scope of access, until the token expires or is revoked. If a refresh token was issued, it may be used to request new access tokens if the original token has expired.

Note Regarding Proof Key for Code Exchange

If a public client is using the Authorization Code grant type, there’s a chance that the authorization code could be intercepted. The Proof Key for Code Exchange (or PKCE, pronounced like “pixie”) is an extension to the Authorization Code flow that helps to mitigate this kind of attack.

The PKCE extension involves the client creating and recording a secret key — known as a code verifier — for every authorization request. The client then transforms the code verifier into a code challenge and then sends this code challenge and the transformation method to the authorization endpoint in the same authorization request.

The authorization endpoint records the code challenge and the transformation method, and responds with the authorization code as outlined previously. The client then sends in the access token request which includes the code verifier it originally generated.

After receiving the code verifier, the authorization server transforms it into the code challenge using the transformation method first shared by the client. If the code challenge derived from the code verifier sent by the client doesn’t match the one originally recorded by the authorization server, then the authorization server will deny the client access.

It’s recommended that every client use the PKCE extension for improved security.

Grant Type: Client Credentials

The client credentials grant type provides an application a way to access its own service account. Examples of when this might be useful include if an application wants to update its registered description or redirect URI, or access other data stored in its service account via the API.

Client Credentials Flow

The application requests an access token by sending its credentials, its client ID and client secret, to the authorization server. An example POST request might look like the following:

https://oauth.example.com/token?grant_type=client_credentials&client_id=CLIENT_ID&client_secret=CLIENT_SECRET

If the application credentials check out, the authorization server returns an access token to the application. Now the application is authorized to use its own account.

Note: DigitalOcean does not currently support the client credentials grant type, so the link points to an imaginary authorization server at oauth.example.com.

Grant Type: Device Code

The device code grant type provides a means for devices that lack a browser or have limited inputs to obtain an access token and access a user’s account. The purpose of this grant type is to make it easier for users to more easily authorize applications on such devices to access their accounts. Examples of when this might be useful include if a user wants to sign into a video streaming application on a device that doesn’t have a typical keyboard input, such as a smart television or a video game console.

Device Code Flow

The user starts an application on their browserless or input-limited device, such as a television or a set-top box. The application submits a POST request to a device authorization endpoint.

An example device code POST request might look like the following:

POST https://oauth.example.com/device

client_id=CLIENT_id

The device authorization endpoint is different from the authentication server, as the device authorization endpoint doesn’t actually authenticate the device. Instead, it returns a unique device code, which is used to identify the device; a user code, which the user can enter on a machine on which it’s easier to authenticate, such as a laptop or mobile device; and the URL the user should visit to enter the user code and authenticate their device.

Here’s what an example response from the device authorization endpoint might look like:

{

"device_code": "IO2RUI3SAH0IQuESHAEBAeYOO8UPAI",

"user_code": "RSIK-KRAM",

"verification_uri": "https://example.okta.com/device",

"interval": 10,

"expires_in": 1600

}

Note that the device code could also be a QR code which the reader can scan on a mobile device.

The user then enters the user code at the specified URL and signs into their account. They are then presented with a consent screen where they can authorize the device to access their account.

While the user visits the verification URL and enters their code, the device will poll the access endpoint until it returns an error or an authentication token. The access endpoint will return errors if the device is polling too frequently (the slow_down error), if the user hasn’t yet approved or denied the request (the authorization_pending error), if the user has denied the request (the access_denied error), or if the token has expired (the expired_token error).

If the user approves the request, though, the access endpoint will return an authentication token.

Note: Again, DigitalOcean does not currently support the device code grant type, so the link in this example points to an imaginary authorization server at oauth.example.com.

Example Access Token Usage

Once the application has an access token, it may use the token to access the user’s account via the API, limited to the scope of access, until the token expires or is revoked.

Here is an example of an API request, using curl. Note that it includes the access token:

curl -X POST -H "Authorization: Bearer ACCESS_TOKEN""https://api.digitalocean.com/v2/$OBJECT"

Assuming the access token is valid, the API will process the request according to its API specifications. If the access token is expired or otherwise invalid, the API will return an invalid_request error.

Refresh Token Flow

After an access token expires, using it to make a request from the API will result in an Invalid Token Error. At this point, if a refresh token was included when the original access token was issued, it can be used to request a fresh access token from the authorization server.

Here is an example POST request, using a refresh token to obtain a new access token:

https://cloud.digitalocean.com/v1/oauth/token?grant_type=refresh_token&client_id=CLIENT_ID&client_secret=CLIENT_SECRET&refresh_token=REFRESH_TOKEN

Conclusion

By following this guide, you will have gained an understanding of how OAuth 2 works, and when a particular authorization flow should be used.

If you want to learn more about OAuth 2, check out these valuable resources:

Thanks for learning with the DigitalOcean Community. Check out our offerings for compute, storage, networking, and managed databases.

About the author

Software Engineer @ DigitalOcean. Former Señor Technical Writer (I no longer update articles or respond to comments). Expertise in areas including Ubuntu, PostgreSQL, MySQL, and more.

Still looking for an answer?

This textbox defaults to using Markdown to format your answer.

You can type !ref in this text area to quickly search our full set of tutorials, documentation & marketplace offerings and insert the link!

Which flow is most suitable for system to system communication using REST APIs?

Good explanation of the Grant Types Re: Your diagrams for Grant Type: Authorization Code Link and Grant Type: Implicit. Step 1. User Authorization Request … is this truly the “User/Resource Owner” request or is this the Application/Client request. The arrow shows the source as Application/Client however the text on the arrow indicates User/Resource Owner. Also the detailed text indicates “User”

@author @manicas Why are you sending sensitive data as Query parameters (in URL), even though it isn’t recommended by the OAuth2 specification itself ? See the last point.

Don’t pass bearer tokens in page URLs: Bearer tokens SHOULD NOT be passed in page URLs (for example as query string parameters). Instead, bearer tokens SHOULD be passed in HTTP message headers or message bodies for which confidentiality measures are taken. Browsers, web servers, and other software may not adequately secure URLs in the browser history, web server logs, and other data structures. If bearer tokens are passed in page URLs, attackers might be able to steal them from the history data, logs, or other unsecured locations.

Thank you guys. This tutorial really helped me understand how OAUTH works. I have a little question though I will like to ask what are the steps or how can I generate a signature for my OAUTH requests as I have read that requests without signature may not be so secured.

Thanks.

- Table of contents

- OAuth Roles

- Abstract Protocol Flow

- Application Registration

- Authorization Grant

- Grant Type: Authorization Code

- Grant Type: Client Credentials

- Grant Type: Device Code

- Example Access Token Usage

- Refresh Token Flow

- Conclusion

Deploy on DigitalOcean

Click below to sign up for DigitalOcean's virtual machines, Databases, and AIML products.

Become a contributor for community

Get paid to write technical tutorials and select a tech-focused charity to receive a matching donation.

DigitalOcean Documentation

Full documentation for every DigitalOcean product.

Resources for startups and SMBs

The Wave has everything you need to know about building a business, from raising funding to marketing your product.

Get our newsletter

Stay up to date by signing up for DigitalOcean’s Infrastructure as a Newsletter.

New accounts only. By submitting your email you agree to our Privacy Policy

The developer cloud

Scale up as you grow — whether you're running one virtual machine or ten thousand.

Get started for free

Sign up and get $200 in credit for your first 60 days with DigitalOcean.*

*This promotional offer applies to new accounts only.