- Log in to:

- Community

- DigitalOcean

- Sign up for:

- Community

- DigitalOcean

Introduction

One capability that almost all servers must have is the power to send and receive information to other networked machines. Although people generally think about servers as providing content (it is in the name after all), they also must have the ability to acquire content for many reasons.

While most Linux packages are available through their distribution’s repositories and can be downloaded with the standard package management tools, other information and files must use other mechanisms. In this guide, we’ll discuss some of the most common methods for getting files and data onto your Linux server.

We will be mainly using an Ubuntu 14.04 VPS instance to run through this list, but you can install and use almost any of this software on other distros and releases.

Acquiring Data and Software from Repositories

Perhaps the most common way of getting packages and software onto your server is through the use of repositories. Repositories in this context can actually refer to fairly different things.

This may simply refer to large collections of available software. These contain compiled and ready to install software that has generally been tested and configured to use with your distribution. There are also source repositories, which contain all of the files necessary to build a certain software project.

We’ll go over both of these types in this section.

Installing Software from a Regular Distribution Repository

The standard way of installing software for a Linux computer is to use a package manager. A package manager is configured to connect to a configured set of servers that contain repositories of packages that have been vetted, packaged, and tested on compatible systems.

Linux distributions use different packaging formats and package managers to accomplish this.

The most popular packaging formats are the .deb packaging format, which is used by Debian and Ubuntu distributions and their derivatives, and the .rpm packaging format, traditionally used by RedHat, CentOS, and Fedora and related distributions. Some systems use different packaging formats. Arch Linux, for instance, uses simple .tar.xz packages.

In general, distributions using .deb packages tend to use the apt package management suite of tools. You can learn about how to use apt to manage .deb packages by clicking here.

Likewise, those distributions using the .rpm package format usually stick with the yum package manager. You can learn how to use yum from a variety of sources, some examples of which are available here, here, and here.

Since Arch Linux doesn’t follow these patterns and uses its own packaging format, it also has developed its own package manager called pacman to manage this functionality. The Arch wiki has a great page on how to use pacman which you can find here.

How to Use Personal Package Archives

One method of acquiring software that is available for Ubuntu machines is the use of personal package archives or PPAs. While this method of getting software is not relevant to most distributions, it does provide flexibility for Ubuntu servers.

A PPA is basically a repository, usually focused on a single or a few specific packages, that is maintained by a person or team outside of the official Ubuntu channels. This allows you to use a PPA as a separate source for your package manager, and the software built and stored there will become available to install seamlessly along with your other packages.

This has some obvious advantages. You can get newer versions of software between official Ubuntu releases, which typically leave you with an older version of most packages for 6 months at a time. They also allow you to easily access software that has not been officially packaged by the Ubuntu team at all, provided that an independent party has taken it upon themselves to provide the packages.

The biggest advantage over compiling from source is that these packages are managed through the normal packaging tools. This means that they can receive updates regularly and are plugged into the general package ecosystem, which allows them to take advantage of features like dependency resolution.

There are, however, disadvantages to this approach as well. For one, you have to place a lot of trust in the maintainers of the PPA that you are using. While you might have good reason to trust the packagers at Ubuntu, you should ask yourself if the PPA you are interested in is provided by a reliable source. There is a possibility that even if the maintainer is not malicious, that they are not the most security conscious and could unknowingly be serving compromised packages.

Another thing to keep in mind is the lifespan of these PPAs. Will you have a plan of action if suddenly the support is dropped from this source? Do you have the time to keep an eye out in case your distribution ends up adding support for the package through the default channels?

Before you get going, you may have to add a package to your system to allow you to easily manage PPAs. This varies by release, but you should be able to use one of the two options below:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install python-software-properties # For Ubuntu 12.04 and lower

sudo apt-get install software-properties-common # For Ubuntu versions > 12.04

Afterwards, you can add a PPA by typing something like this:

<pre> sudo add-apt-repository ppa:<span class=“highlight”>PPA_name</span> </pre>

You then would want to update your package index to pull information from your new PPA. You can then install any new software that the PPA provides:

<pre> sudo apt-get update sudo apt-get install <span class=“highlight”>new_package</span> </pre>

Git Repositories

The other type of repository that you’re likely to come across while dealing with Linux software is used to manage software source files. Generally, this means git repositories.

If the files that you are interested are hosted in a git repository, or on a hosted Git solution like GitHub, Bitbucket, private GitLab, etc. you can easily pull down the files using conventional git commands.

Ensure that your server has git installed to begin:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install git

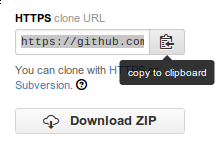

Afterwards, you can simply move to the directory where you’d like to keep the project and clone the repository using the provided information on the site. For instance, on GitHub, you can get a project’s repository URL along the right-hand side:

You can copy the URL, and paste it into your terminal session after the clone command:

<pre> git clone <span class=“highlight”>https://github.com/user/project.git</span> </pre>

This will clone the project in its entirety into your current directory.

General Web Resources

While managing software with repositories is easy and provides a great method for keeping track of software and changes, it is not always possible to rely on these methods for a variety of reasons. Not all software is kept in repositories, and software packages are not the only kind of data you probably want on your server.

For non-repository content, we have other tools that can assist us. We’ll discuss some sophisticated and unsophisticated methods below.

Remote Download and Transfer

Perhaps the way of getting data onto your server that feels the most natural is to download data to your home computer and then upload it to the site. Since you are probably already uploading custom content to your site, this method, if not exactly elegant, is easy.

Any content, files, or packages that you would like on your site can be downloaded to your computer using a normal web browser. Make sure that if you are getting software, that you are downloading the correct version to match your server’s distribution, release, and architecture (if the download options are distinct).

Afterwards, you can easily transfer these files to your server. The recommended method is through an sftp connection, which will allow you to securely transfer data easily. You can use sftp from the command line like we show in this guide, or you can use an FTP client with sftp capabilities, as we show in this guide about using FileZilla with sftp.

This is probably the most flexible way of getting content onto your server, because it allows you to transfer files that you have created in addition to files you have access to on the web.

Console-Based Web Browsers

Another interesting way of getting content onto your system is to actually use a web browser from within the server.

While you can install entire graphical display servers and conventional browsers onto your server, this is almost always overkill and not necessary. An alternative is to use console-based web browsers that allow you to visit a website that is displayed in a text-only output.

There are quite a few options available for console-based web browsers.

lynx

The lynx browser is the oldest web browser that is still actively in development and in use. It is also easy to use. Basically, using the UP and DOWN arrow keys allows you to easily jump between links throughout the page. To follow a link, press ENTER or the RIGHT arrow when its entry is highlighted.

This may not be available on your system by default, but you can install it easily by typing something like:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install lynx

Lynx can handle cookie management and bookmarks. It can render colored output if your terminal supports it. It generally can be used for any website that does not rely on things like javascript to provide actual functionality.

Here, for example, you can see a sample DigitalOcean account page rendered in the lynx browser:

Droplets

Create Droplet

× Logged in!

Image Name IP Address Status Memory Disk Region

irssi xxx.241.xxx.54 Active 512MB 20GB nyc1

try 192.xxx.170.xx Active 4GB 60GB nyc2

snmp xxx.170.xx.123 Active 4GB 60GB nyc2

tugboat 192.xxx.162.xxx Active 4GB 60GB nyc2

As you can see, this is fairly usable.

links

This browser is also great at browsing the web from the command line. One feature of the links browser over something like lynx is that it contains a menu system similar to a traditional browser that can be accessed by hitting the ESC key.

You can get this browser if its not already on your system by typing:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install links

While the links browser does not render colored text in its default configuration, making it slightly harder to distinguish hyper links, it takes advantage of a lot of ncurses features to make rendering look fairly nice. Putting a graphical site into text will always cause formatting issues, but links does a pretty nice job:

Droplets

Create Droplet

Image Name IP Address Status Memory Disk Region

irssi xxx.241.xxx.54 Active 512MB 20GB nyc1

try 192.xxx.170.xx Active 4GB 60GB nyc2

snmp xxx.170.xx.123 Active 4GB 60GB nyc2

tugboat 192.xxx.162.xxx Active 4GB 60GB nyc2

Another feature that may influence your decision is that links by default incorporates mouse support, meaning that you can click links in your terminal window just like you would in your regular browser.

elinks

A popular fork of the links browser is elinks. This fork was started in 2001 and incorporates an extended feature set while leveraging the links rendering mechanisms and the underlying engine.

To get elinks on an Ubuntu machine, you can type:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install elinks

Some of the features you get from elinks over links are password and form management, tabbed browsing, partial javascript support, and bittorrent and IPv6 protocol support. These may come at the cost of speed, but most likely this will not be too noticeable.

w3m

This is another full featured text browser which may be easier to use in the same way that you would use a graphical browser. Most of the other browsers on this list allow you to jump between links, but make it difficult to browse the page itself. The w3m browser, however, uses TABs to navigate between links and arrow keys to move the cursor independently to scroll the page.

While many systems include w3m by default, if your server doesn’t have this browser, you can add it by typing:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install w3m

Another advantage of this browser that will interest some people is that it can use vi-like key commands. For instance, you can also move the cursor by typing, ‘j’, ‘k’, ‘l’, and ‘h’.

Download Utilities

While sometimes it is helpful to be able to browse from the server itself, more often, you will find that browsing from a graphical web browser on your own machine is more efficient and will allow you to render the pages in a more faithful manner.

Because of this, many people browse the web on their own machine and then paste download links into their terminal window to use with downloading utilities.

wget

The wget tool is a great option for quickly getting pages or downloads from a website.

If you do not have wget already available on your Ubuntu server, you can acquire it by typing:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install wget

Afterwards, downloading a file from a remote source is as easy as pasting the URL after the command name like this:

<pre> wget <span class=“highlight”>www.example.com</span> </pre>

If you point this at a general website, it will download the index or main page to a file in the local directory. If you direct it towards a file, it will download the file instead.

Usually, the process would be to use the browser on your home computer to find a file on the internet that you are interested in, right-click on the link to the download, and select the option similar to “copy link location”. Then you would use this URL with the above command.

If your download gets interrupted, you actually can actually use the -c flag, which will resume a partial download if an incomplete file is found in the current directory:

<pre> wget -c <span class=“highlight”>www.example.com</span> </pre>

The wget command can handle cookies, is a good candidate for scripting, and can recursively download entire websites in their original format.

curl

The curl tool is also a great choice for this type of operation. While wget usually operates by producing files, curl by default uses standard output, making it incredibly useful for scripts and pipes. It also supports a great number of protocols, and can handle more HTTP authentication methods than wget.

While many systems will have curl installed by default, if your Ubuntu machine does not, you can type:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install curl

While curl uses pipes normally, you can easily have it save its output to a file as well. This is what you probably want if you are downloading files for your server. To download a file and output it to a local file with the same name, type:

<pre> curl -O <span class=“highlight”>www.example.com/index.html</span> </pre>

We have to specify a file because that is how curl will know what to name the local file.

If we want to choose what to name the local file, we no longer need to point it at a specific file if we are looking for the directory index of a site. Instead we can optionally point it at a location and whatever index file is configured to return will be placed in the file we choose:

<pre> curl -o file.html <span class=“highlight”>www.example.com</span> </pre>

This works just as well for downloading a file to a name you want to choose and is not only useful for working with directory indexes.

If you are handed a redirect, you can tell curl to follow it by also using the -L flag.

Conclusion

By now, you can see that there are quite a few different options for getting software, data, and material from the internet onto your server. While all of these have the ability to pull content from the web, none of them are suitable for every kind of downloading and consuming.

It is helpful to know what your options are and to be able to leverage the strengths of each solution for the situations that it was designed for. This will help you avoid doing unnecessary work and will give you flexibility in the way that you approach a problem.

<div class=“author”>By Justin Ellingwood</div>

Thanks for learning with the DigitalOcean Community. Check out our offerings for compute, storage, networking, and managed databases.

About the author

Former Senior Technical Writer at DigitalOcean, specializing in DevOps topics across multiple Linux distributions, including Ubuntu 18.04, 20.04, 22.04, as well as Debian 10 and 11.

Still looking for an answer?

This textbox defaults to using Markdown to format your answer.

You can type !ref in this text area to quickly search our full set of tutorials, documentation & marketplace offerings and insert the link!

Deploy on DigitalOcean

Click below to sign up for DigitalOcean's virtual machines, Databases, and AIML products.

Become a contributor for community

Get paid to write technical tutorials and select a tech-focused charity to receive a matching donation.

DigitalOcean Documentation

Full documentation for every DigitalOcean product.

Resources for startups and SMBs

The Wave has everything you need to know about building a business, from raising funding to marketing your product.

Get our newsletter

Stay up to date by signing up for DigitalOcean’s Infrastructure as a Newsletter.

New accounts only. By submitting your email you agree to our Privacy Policy

The developer cloud

Scale up as you grow — whether you're running one virtual machine or ten thousand.

Get started for free

Sign up and get $200 in credit for your first 60 days with DigitalOcean.*

*This promotional offer applies to new accounts only.