- Log in to:

- Community

- DigitalOcean

- Sign up for:

- Community

- DigitalOcean

Introduction

Django is a powerful web framework that can help you get your Python application or website off the ground. Django includes a simplified development server for testing your code locally, but for anything even slightly production related, a more secure and powerful web server is required.

In this guide, we will demonstrate how to install and configure some components on Ubuntu 14.04 to support and serve Django applications. We will configure the uWSGI application container server to interface with our applications. We will then set up Nginx to reverse proxy to uWSGI, giving us access to its security and performance features to serve our apps.

Prerequisites and Goals

In order to complete this guide, you should have a fresh Ubuntu 14.04 server instance with a non-root user with sudo privileges configured. You can learn how to set this up by running through our initial server setup guide.

We will be installing Django within two different virtual environments. This will allow your projects and their requirements to be handled separately. We will be creating two sample projects so that we can run through the steps in a multi-project environment.

Once we have our applications, we will install and configure the uWSGI application server. This will serve as an interface to our applications which will translate client requests using HTTP to Python calls that our application can process. We will then set up Nginx in front of uWSGI to take advantage of its high performance connection handling mechanisms and its easy-to-implement security features.

Let’s get started.

Install and Configure VirtualEnv and VirtualEnvWrapper

We will be installing our Django projects in their own virtual environments to isolate the requirements for each. To do this, we will be installing virtualenv, which can create Python virtual environments, and virtualenvwrapper, which adds some usability improvements to the virtualenv work flow.

We will be installing both of these components using pip, the Python package manager. This can be acquired from the Ubuntu repositories:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install python-pip

In this guide, we are using Python version 2. If your code uses Python 3, you can install the python3-pip package. You will then have to substitute the pip commands in this guide with the pip3 command when operating outside of a virtual environment.

Now that you have pip installed, we can install virtualenv and virtualenvwrapper globally by typing:

sudo pip install virtualenv virtualenvwrapper

With these components installed, we can now configure our shell with the information it needs to work with the virtualenvwrapper script. Our virtual environments will all be placed within a directory in our home folder called Env for easy access. This is configured through an environmental variable called WORKON_HOME. We can add this to our shell initialization script and can source the virtual environment wrapper script.

If you are using Python 3 and the pip3 command, you will have to add an additional line to your shell initialization script as well:

echo "export VIRTUALENVWRAPPER_PYTHON=/usr/bin/python3" >> ~/.bashrc

Regardless of which version of Python you are using, you need to run the following commands:

echo "export WORKON_HOME=~/Env" >> ~/.bashrc

echo "source /usr/local/bin/virtualenvwrapper.sh" >> ~/.bashrc

Now, source your shell initialization script so that you can use this functionality in your current session:

source ~/.bashrc

You should now have directory called Env in your home folder which will hold virtual environment information.

Create Django Projects

Now that we have our virtual environment tools, we will create two virtual environments, install Django in each, and start two projects.

Create the First Project

We can create a virtual environment easily by using some commands that the virtualenvwrapper script makes available to us.

Create your first virtual environment with the name of your first site or project by typing:

mkvirtualenv firstsite

This will create a virtual environment, install Python and pip within it, and activate the environment. Your prompt will change to indicate that you are now operating within your new virtual environment. It will look something like this: (firstsite)user@hostname:~$. The value in the parentheses is the name of your virtual environment. Any software installed through pip will now be installed into the virtual environment instead of on the global system. This allows us to isolate our packages on a per-project basis.

Our first step will be to install Django itself. We can use pip for this without sudo since we are installing this locally in our virtual environment:

pip install django

With Django installed, we can create our first sample project by typing:

cd ~

django-admin.py startproject firstsite

This will create a directory called firstsite within your home directory. Within this is a management script used to handle various aspects of the project and another directory of the same name used to house the actual project code.

Move into the first level directory so that we can begin setting up the minimum requirements for our sample project.

cd ~/firstsite

Begin by migrating the database to initialize the SQLite database that our project will use. You can set up an alternative database for your application if you wish, but this is outside of the scope of this guide:

./manage.py migrate

You should now have a database file called db.sqlite3 in your project directory. Now, we can create an administrative user by typing:

./manage.py createsuperuser

You will have to select a username, give a contact email address, and then select and confirm a password.

Next, open the settings file for the project with your text editor:

nano firstsite/settings.py

Since we will be setting up Nginx to serve our site, we need to configure a directory which will hold our site’s static assets. This will allow Nginx to serve these directly, which will have a positive impact on performance. We will tell Django to place these into a directory called static in our project’s base directory. Add this line to the bottom of the file to configure this behavior:

STATIC_ROOT = os.path.join(BASE_DIR, "static/")

Save and close the file when you are finished. Now, collect our site’s static elements and place them within that directory by typing:

./manage.py collectstatic

You can type “yes” to confirm the action and collect the static content. There will be a new directory called static in your project directory.

With all of that out of the way, we can test our project by temporarily starting the development server. Type:

./manage.py runserver 0.0.0.0:8080

This will start up the development server on port 8080. Visit your server’s domain name or IP address followed by 8080 in your browser:

http://server_domain_or_IP:8080

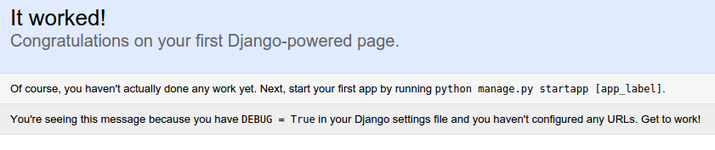

You should see a page that looks like this:

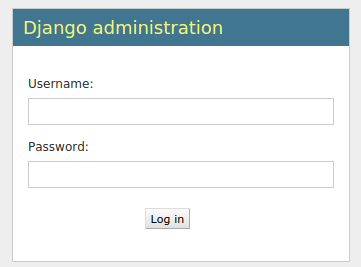

Add /admin to the end of the URL in your browser’s address bar and you will be taken to the admin login page:

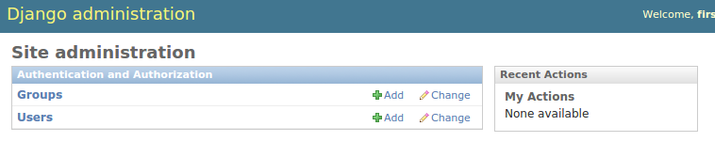

Using the administrative login credentials you selected with the createsuperuser command, log into the server. You will then have access to the administration interface:

After testing this functionality out, stop the development server by typing CTRL-C in your terminal. We can now move on to our second project.

Create the Second Project

The second project will be created in exactly the same way as the first. We will abridge the explanation in this section, seeing as how you have already completed this once.

Move back to your home directory and create a second virtual environment for your new project. Install Django inside of this new environment once it is activated:

cd ~

mkvirtualenv secondsite

pip install django

The new environment will be created and changed to, leaving your previous virtual environment. This Django instance is entirely separate from the other one you configured. This allows you to manage them independently and customize as necessary.

Create the second project and move into the project directory:

django-admin.py startproject secondsite

cd ~/secondsite

Initialize the database and create an administrative user:

./manage.py migrate

./manage.py createsuperuser

Open the settings file:

nano secondsite/settings.py

Add the location for the static files, just as you did in the previous project:

STATIC_ROOT = os.path.join(BASE_DIR, "static/")

Save and close the file. Now, collect the static elements into that directory by typing:

./manage.py collectstatic

Finally, fire up the development server to test out the site:

./manage.py runserver 0.0.0.0:8080

You should check the regular site at:

http://server_domain_or_IP:8080

Also log into the admin site:

http://server_domain_or_IP:8080/admin

When you’ve confirmed that everything is working as expected, type CTRL-C in your terminal to stop the development server.

Backing Out of the Virtual Environment

Since we are now done with the Django portion of the guide, we can deactivate our second virtual environment:

deactivate

If you need to work on either of your Django sites again, you should reactivate their respective environments. You can do that by using the workon command:

workon firstsite

Or:

workon secondsite

Again, deactivate when you are finished working on your sites:

deactivate

Setting up the uWSGI Application Server

Now that we have two Django projects set up and ready to go, we can configure uWSGI. uWSGI is an application server that can communicate with applications over a standard interface called WSGI. To learn more about this, read this section of our guide on setting up uWSGI and Nginx on Ubuntu 14.04.

Installing uWSGI

Unlike the guide linked above, in this tutorial, we’ll be installing uWSGI globally. This will create less friction in handling multiple Django projects. Before we can install uWSGI, we need the Python development files that the software relies on. We can install this directly from Ubuntu’s repositories:

sudo apt-get install python-dev

Now that the development files are available, we can install uWSGI globally through pip by typing:

sudo pip install uwsgi

We can quickly test this application server by passing it the information for one of our sites. For instance, we can tell it to serve our first project by typing:

uwsgi --http :8080 --home /home/user/Env/firstsite --chdir /home/user/firstsite -w firstsite.wsgi

Here, we’ve told uWSGI to use our virtual environment located in our ~/Env directory, to change to our project’s directory, and to use the wsgi.py file stored within our inner firstsite directory to serve the file. For our demonstration, we told it to serve HTTP on port 8080. If you go to server’s domain name or IP address in your browser, followed by :8080, you will see your site again (the static elements in the /admin interface won’t work yet). When you are finished testing out this functionality, type CTRL-C in the terminal.

Creating Configuration Files

Running uWSGI from the command line is useful for testing, but isn’t particularly helpful for an actual deployment. Instead, we will run uWSGI in “Emperor mode”, which allows a master process to manage separate applications automatically given a set of configuration files.

Create a directory that will hold your configuration files. Since this is a global process, we will create a directory called /etc/uwsgi/sites to store our configuration files. Move into the directory after you create it:

sudo mkdir -p /etc/uwsgi/sites

cd /etc/uwsgi/sites

In this directory, we will place our configuration files. We need a configuration file for each of the projects we are serving. The uWSGI process can take configuration files in a variety of formats, but we will use .ini files due to their simplicity.

Create a file for your first project and open it in your text editor:

sudo nano firstsite.ini

Inside, we must begin with the [uwsgi] section header. All of our information will go beneath this header. We are also going to use variables to make our configuration file more reusable. After the header, set a variable called project with the name of your first project. Add a variable called base with the path to your user’s home directory:

[uwsgi]

project = firstsite

base = /home/user

Next, we need to configure uWSGI so that it handles our project correctly. We need to change into the root project directory by setting the chdir option. We can combine the home directory and project name setting that we set earlier by using the %(variable_name) syntax. This will be replaced by the value of the variable when the config is read.

In a similar way, we will indicate the virtual environment for our project. By setting the module, we can indicate exactly how to interface with our project (by importing the “application” callable from the wsgi.py file within our project directory). The configuration of these items will look like this:

[uwsgi]

project = firstsite

base = /home/user

chdir = %(base)/%(project)

home = %(base)/Env/%(project)

module = %(project).wsgi:application

We want to create a master process with 5 workers. We can do this by adding this:

[uwsgi]

project = firstsite

base = /home/user

chdir = %(base)/%(project)

home = %(base)/Env/%(project)

module = %(project).wsgi:application

master = true

processes = 5

Next we need to specify how uWSGI should listen for connections. In our test of uWSGI, we used HTTP and a network port. However, since we are going to be using Nginx as a reverse proxy, we have better options.

Instead of using a network port, since all of the components are operating on a single server, we can use a Unix socket. This is more secure and offers better performance. This socket will not use HTTP, but instead will implement uWSGI’s uwsgi protocol, which is a fast binary protocol for designed for communicating with other servers. Nginx can natively proxy using the uwsgi protocol, so this is our best choice.

We will also modify the permissions of the socket because we will be giving the web server write access. We’ll set the vacuum option so that the socket file will be automatically cleaned up when the service is stopped:

[uwsgi]

project = firstsite

base = /home/user

chdir = %(base)/%(project)

home = %(base)/Env/%(project)

module = %(project).wsgi:application

master = true

processes = 5

socket = %(base)/%(project)/%(project).sock

chmod-socket = 664

vacuum = true

With this, our first project’s uWSGI configuration is complete. Save and close the file.

The advantage of setting up the file using variables is that it makes it incredibly simple to reuse. Copy your first project’s configuration file to use as a base for your second configuration file:

sudo cp /etc/uwsgi/sites/firstsite.ini /etc/uwsgi/sites/secondsite.ini

Open the second configuration file with your text editor:

sudo nano /etc/uwsgi/sites/secondsite.ini

We only need to change a single value in this file in order to make it work for our second project. Modify the project variable with the name you’ve used for your second project:

[uwsgi]

project = secondsite

base = /home/user

chdir = %(base)/%(project)

home = %(base)/Env/%(project)

module = %(project).wsgi:application

master = true

processes = 5

socket = %(base)/%(project)/%(project).sock

chmod-socket = 664

vacuum = true

Save and close the file when you are finished. Your second project should be ready to go now.

Create an Upstart Script for uWSGI

We now have the configuration files we need to serve our Django projects, but we still haven’t automated the process. Next, we’ll create an Upstart script to automatically start uWSGI at boot.

We will create an Upstart script in the /etc/init directory, where these files are checked:

sudo nano /etc/init/uwsgi.conf

Start by setting a description for your uWSGI service and indicating the runlevels where it should automatically run. We will set ours to run on runlevels 2, 3, 4, and 5, which are the conventional multi-user runlevels:

description "uWSGI application server in Emperor mode"

start on runlevel [2345]

stop on runlevel [!2345]

Next, we need to set the username and group that the process will be run as. We will run the process under our own username since we own all of the files. For the group, we need to set it to the www-data group that Nginx will run under. Our socket settings from the uWSGI configuration file should then allow the web server to write to the socket. Change the username below to match your username on the server:

description "uWSGI application server in Emperor mode"

start on runlevel [2345]

stop on runlevel [!2345]

setuid user

setgid www-data

Finally, we need to specify the actual command to execute. We need to start uWSGI in Emperor mode and pass in the directory where we stored our configuration files. uWSGI will read the files and serve each of our projects:

description "uWSGI application server in Emperor mode"

start on runlevel [2345]

stop on runlevel [!2345]

setuid user

setgid www-data

exec /usr/local/bin/uwsgi --emperor /etc/uwsgi/sites

When you are finished, save and close the file. We won’t start uWSGI yet since we will not have the www-data group available until after we install Nginx.

Install and Configure Nginx as a Reverse Proxy

With uWSGI configured and ready to go, we can now install and configure Nginx as our reverse proxy. This can be downloaded from Ubuntu’s default repositories:

sudo apt-get install nginx

Once Nginx is installed, we can go ahead and create a server block configuration file for each of our projects. Start with the first project by creating a server block configuration file:

sudo nano /etc/nginx/sites-available/firstsite

Inside, we can start our server block by indicating the port number and domain name where our first project should be accessible. We’ll assume that you have a domain name for each:

server {

listen 80;

server_name firstsite.com www.firstsite.com;

}

Next, we can tell Nginx not to worry if it can’t find a favicon. We will also point it to the location of our static files directory where we collected our site’s static elements:

server {

listen 80;

server_name firstsite.com www.firstsite.com;

location = /favicon.ico { access_log off; log_not_found off; }

location /static/ {

root /home/user/firstsite;

}

}

After that, we can use the uwsgi_pass directive to pass the traffic to our socket file. The socket file that we configured was called firstproject.sock and it was located in our project directory. We will use the include directive to include the necessary uwsgi parameters to handle the connection:

server {

listen 80;

server_name firstsite.com www.firstsite.com;

location = /favicon.ico { access_log off; log_not_found off; }

location /static/ {

root /home/user/firstsite;

}

location / {

include uwsgi_params;

uwsgi_pass unix:/home/user/firstsite/firstsite.sock;

}

}

That is actually all the configuration we need. Save and close the file when you are finished.

We will use this as a basis for our second project’s Nginx configuration file. Copy it over now:

sudo cp /etc/nginx/sites-available/firstsite /etc/nginx/sites-available/secondsite

Open the new file in your text editor:

sudo nano /etc/nginx/sites-available/secondsite

Here, you’ll have to change any reference to firstsite with a reference to secondsite. You’ll also have to modify the server_name so that your second project responds to a different domain name. When you are finished, it will look something like this:

server {

listen 80;

server_name secondsite.com www.secondsite.com;

location = /favicon.ico { access_log off; log_not_found off; }

location /static/ {

root /home/user/secondsite;

}

location / {

include uwsgi_params;

uwsgi_pass unix:/home/user/secondsite/secondsite.sock;

}

}

Save and close the file when you are finished.

Next, link both of your new configuration files to Nginx’s sites-enabled directory to enable them:

sudo ln -s /etc/nginx/sites-available/firstsite /etc/nginx/sites-enabled

sudo ln -s /etc/nginx/sites-available/secondsite /etc/nginx/sites-enabled

Check the configuration syntax by typing:

sudo service nginx configtest

If no syntax errors are detected, you can restart your Nginx service to load the new configuration:

sudo service nginx restart

If you remember from earlier, we never actually started the uWSGI server. Do that now by typing:

sudo service uwsgi start

You should now be able to reach your two projects by going to their respective domain names. Both the public and administrative interfaces should work as expected.

Conclusion

In this guide, we’ve set up two Django projects, each in their own virtual environments. We’ve configured uWSGI to serve each project independently using the virtual environment configured for each. Afterwards, we set up Nginx to act as a reverse proxy to handle client connections and serve the correct project depending on the client request.

Django makes creating projects and applications simple by providing many of the common pieces, allowing you to focus on the unique elements. By leveraging the general tool chain described in this article, you can easily serve the applications you create from a single server.

Thanks for learning with the DigitalOcean Community. Check out our offerings for compute, storage, networking, and managed databases.

About the author

Former Senior Technical Writer at DigitalOcean, specializing in DevOps topics across multiple Linux distributions, including Ubuntu 18.04, 20.04, 22.04, as well as Debian 10 and 11.

Still looking for an answer?

This textbox defaults to using Markdown to format your answer.

You can type !ref in this text area to quickly search our full set of tutorials, documentation & marketplace offerings and insert the link!

Works! Great tutorial! Have one question: I use env. variable in my settings.py like os.environ.get(‘DB_NAME’), but they are not working. Any idea why they dont work?

Hi there,

Followed this tutorial to the T (great job by the way!). However, I am getting a 502 bad gateway error. I got to the part with the Django server, and it worked correctly, its the UWSGI config that must’ve caused the 502. Any ideas?

Like @tbrightbill, i get a 502 error. Seems like it can’t create the socket. https://gist.github.com/anonymous/40284b9c84bea2df6fca

This comment has been deleted

I was able to make the uwsgi start using uwsgi --http :8080 --home /home/user/Env/firstsite --chdir /home/user/firstsite -w firstsite.wsgi

I was not able to start using uwsgi configuration file, there is no port mention in the uwsgi config file.

Where is the use of setgid www-data?

How to mention server name in nginx if I have IP address ?

Hi there,

I have followed your setup.

The issue I continue to have is that only the firstsite.sock (in my case, it’s called djangoonpy2.sock) is showing up. The secondsite.sock is NOT.

These are my following files:

/etc/nginx/sites-enabled/djangoonpy2.conf

server {

listen 80;

server_name djangoonpy2.app;

location = favicon.ico { access_log off; log_not_found off; }

location /static/ {

root /src/Apps/djangoonpy2;

}

location / {

include uwsgi_params;

uwsgi_pass unix:/run/uwsgi/djangoonpy2.sock;

}

}

/etc/nginx/sites-enabled/djangoonpy3.conf

server {

listen 80;

server_name djangoonpy3.app;

location = favicon.ico { access_log off; log_not_found off; }

location /static/ {

root /src/Apps/djangoonpy3;

}

location / {

include uwsgi_params;

uwsgi_pass unix:/run/uwsgi/djangoonpy3.sock;

}

}

/etc/init/uwsgi.conf

description "uWSGI application server in Emperor mode"

start on runlevel [2345]

stop on runlevel [!2345]

respawn

pre-start script

mkdir -p /run/uwsgi

chown vagrant:www-data /run/uwsgi

end script

exec /usr/local/bin/uwsgi --emperor /etc/uwsgi/sites

/etc/uwsgi/sites/djangoonpy2.ini

[uwsgi]

project = djangoonpy2

username = vagrant

projectbase = /src/Apps

userbase = /home/%(username)

chdir = %(projectbase)/%(project)

home = %(userbase)/.virtualenvs/%(project)

module = %(project).wsgi:application

master = true

processes = 5

uid = %(username)

socket = /run/uwsgi/%(project).sock

chown-socket = %(username):www-data

chmod-socket = 664

vacuum = true

/etc/uwsgi/sites/djangoonpy3.ini

[uwsgi]

project = djangoonpy3

username = vagrant

projectbase = /src/Apps

userbase = /home/%(username)

chdir = %(projectbase)/%(project)

home = %(userbase)/.virtualenvs/%(project)

module = %(project).wsgi:application

master = true

processes = 5

uid = %(username)

socket = /run/uwsgi/%(project).sock

chown-socket = %(username):www-data

chmod-socket = 664

vacuum = true

I have also done:

sudo usermod -a -G vagrant www-data

I have also chmod /src/Apps as 755

Why did I use /run/uwsgi?

Because for some reason using /home/username just doesn’t work.

UPDATE

I tried uwsgi --http :8080 --home ~/.virtualenvs/djangoonpy2 --chdir /src/Apps/djangoonpy2 -w djangoonpy2.wsgi

which works

I tried uwsgi --http :8080 --home ~/.virtualenvs/djangoonpy3 --chdir /src/Apps/djangoonpy3 -w djangoonpy3.wsgi

which failed because I get a ImportError no module named site

I surmised this has to do with the fact that the global uwsgi is for python2.

So I removed djangoonpy3.ini from /etc/uwsgi/sites and then proceeded to create another virtualenv, another project, etc named seconddjangoonpy2

this time it worked.

My question is, how do I run multiple django apps using uwsgi and nginx on ubuntu 14.04 where one of them is on python 3 and the rest are on python 2?

Hi, Thanks for tutorial. I followed all the steps, but when i run

sudo service uwsgi start

I got the following error:

Failed to start uwsgi.service: Unit uwsgi.service failed to load: No such file or directory.

I am running Ubuntu 15.04. Is that the problem?

my uswgi.conf file is:

description "uWSGI application server in Emperor mode"

start on runlevel [2345]

stop on runlevel [!2345]

setuid rijo

setgid www-data

exec /usr/local/bin/uwsgi --emperor /etc/uwsgi/sites/ --logto /var/log/uwsgi.log

my ini file is:

[uwsgi]

project = mysterybox

base = /home/rijo

chdir = %(base)/%(project)

home = %(base)/Env/%(project)

module = %(project).wsgi:application

master = true

processes = 5

socket = %(base)/%(project)/%(project).sock

chmod-socket = 664

vacuum = true

Thanks :)

- Table of contents

- Prerequisites and Goals

- Install and Configure VirtualEnv and VirtualEnvWrapper

- Create Django Projects

- Setting up the uWSGI Application Server

- Install and Configure Nginx as a Reverse Proxy

- Conclusion

Deploy on DigitalOcean

Click below to sign up for DigitalOcean's virtual machines, Databases, and AIML products.

Become a contributor for community

Get paid to write technical tutorials and select a tech-focused charity to receive a matching donation.

DigitalOcean Documentation

Full documentation for every DigitalOcean product.

Resources for startups and SMBs

The Wave has everything you need to know about building a business, from raising funding to marketing your product.

Get our newsletter

Stay up to date by signing up for DigitalOcean’s Infrastructure as a Newsletter.

New accounts only. By submitting your email you agree to our Privacy Policy

The developer cloud

Scale up as you grow — whether you're running one virtual machine or ten thousand.

Get started for free

Sign up and get $200 in credit for your first 60 days with DigitalOcean.*

*This promotional offer applies to new accounts only.